Every once in a while, a breathless headline promises that some new discovery will turn upside-down everything you ever knew about Christianity. Bible students know to treat such claims with great skepticism. If you are patient, it won’t be long before the claim is exposed as being much less than what it was advertised to be, or even exposed as being fraudulent. This very recent story is one such case. It provides an instructive look at the prejudices and predilections of Bible critics.

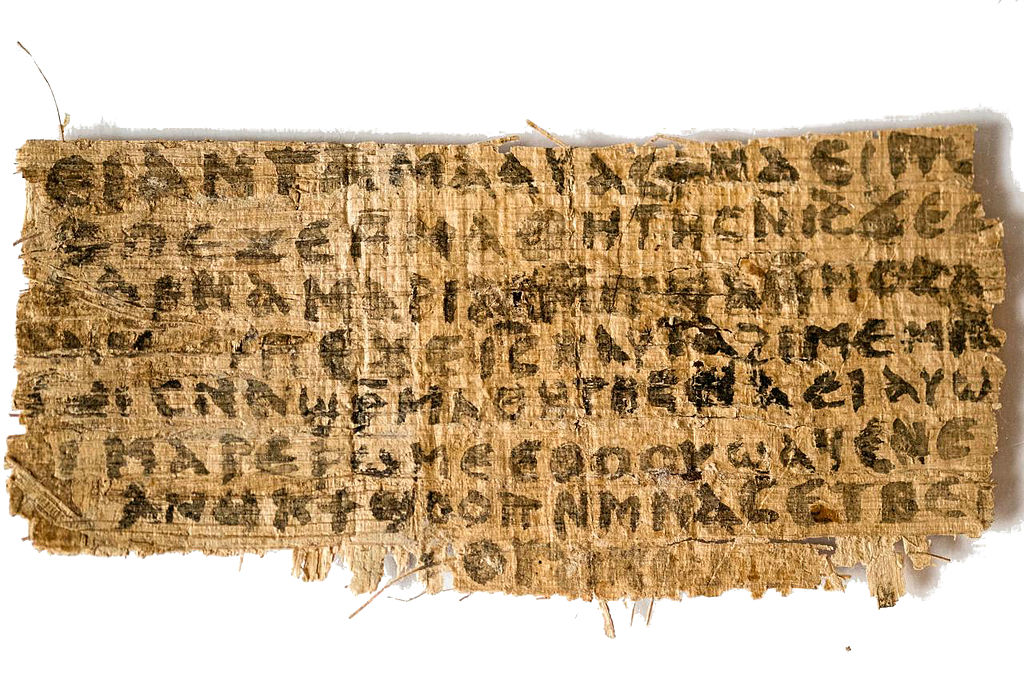

The controversial text was revealed to the world in a conference held in the shadow of Vatican City on September 18, 2012. Dr. Karen King, an American woman who is the prestigious Hollis Professor of Divinity (Harvard University’s oldest endowed professorship dating back to 1721) presented to an audience of 300 scholars a scrap of ancient papyrus no larger than a business card. An anonymous owner had lent her this fragment containing writing in the ancient Egyptian Coptic language. The text was incomplete but what remained contained the following partial sentences:

- …not [to] me. My mother gave me life …

- … The disciples said to Jesus, …

- …deny. Mary is (not?) worthy of it. …

- …Jesus said to them, “My wife …

- … she is able to be my disciple …

- … Let wicked people swell up …

- … As for me, I am with her in order to …

- … an image …

Professor King’s interpretation was that the “wife” Jesus referred to was probably Mary Magdalene. She said the fragment was not evidence that Jesus was married but it demonstrated that some early Christians believed that he was.

It was a news sensation! News outlets around the world, reported the discovery of this ancient text that seemed to suggest Jesus was married. Prestigious magazines such as National Geographic and the Smithsonian Magazine gave it broad coverage. Professor King gave the fragment the attention-grabbing name, “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife”. This was bold, because it deliberately put the 8 line fragment the same category as the 4 Gospel books of the Christian Greek Scriptures (the “New Testament”).

But wait! This all sounds familiar. Where have we heard this story before? In 2003, American writer Dan Brown published a historical-mystery thriller called, “The Da Vinci Code”. For the next few years the book was everywhere, outselling even the Harry Potter books. In 2006 the book was made into a movie starring Tom Hanks. It was the second highest grossing film of the year. The fact that the majority of literary and film critics hated the book and the film* mattered not at all. They were both smash hits.

What made the book different from other thrillers was that it claimed to be based on a historically accurate premise. Dan Brown claimed repeatedly in early interviews that the historical background of the novel was entirely factual. Those claims helped drive sales for the book and the inevitable controversy surrounding those claims helped publicize it to a far larger audience. There is no doubt that many people who read the book believed those claims.

Among the claims the book made was the unscriptural assertion that Jesus never died at Roman hands but was rescued by his disciples. He then married Mary Magdalene and lived with her for the remainder of his life, secretly fathering many children. Those children became the ancestors of the Merovingian kings of France! Further, Brown claimed that early disciples of Jesus worshiped Mary Magdalene as the “divine feminine”.

As baseless as those claims were, Brown’s book was not to the first to assert them. The “Married Jesus” hypothesis was invented in a 1982 revisionist history/conspiracy book entitled, “The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail”. In fact the authors unsuccessfully sued Dan Brown for copyright infringement in 2006.

By 2012 Da Vinci hysteria had died down but Dr. Karen King deliberately appealed to it by naming her scrap of parchment “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife”**. The title had the desired effect. It brought the attention of the media. For example, the Guardian newspaper of England asked, “Does the Jesus ‘wife’ evidence change anything for Christianity?” Was the parchment historical evidence at last for Dan Brown’s work of fiction?

Critical voices in academia were quick to express skepticism. Some of the first objections were on paleographical grounds (palaeography is the study, dating and deciphering of ancient manuscripts). Not long after the conference in Rome, New Testament scholar Craig A. Evens wrote, “I suspect the papyrus itself is probably quite old, perhaps fourth or fifth century, but the oddly written (or painted) letters on the recto side are probably modern and probably reflect recent interest in Jesus and Mary Magdalene.” Professor Francis Watson, of Durham University said that the fragment is a patchwork of texts from a well-known Coptic-language document called the “Gospel of Thomas”***, which have been reassembled out-of-order to make a new sounding document. Leo Depuydt, a Professor of Egyptology and Assyriology at Brown University did not hold back his true feelings about the so-called “Gospel”. Quoted in the Washington Post, Depuydt described the authors use of bold letters for the word “My” as, “almost hilarious.” He continued, “The effect is something like: ‘My wife. Get it? MY wife. You heard that right.’ The papyrus fragment seems ripe for a Monty Python sketch…. If the forger had used italics in addition, one might be in danger of losing one’s composure.”

The next nail in the “Gospel’s” coffin followed quickly. Professor Watson had suggested that fragment was cobbled together from quotes mined from another ancient pseudo-Christian document called the “Gospel of Thomas”. Other scholars came to the same conclusion. In fact, the sentences on the fragment bear a striking resemblance to the only known Coptic translation of the “Gospel of Thomas”. In 2002, this version of the Gospel of Thomas was published on the Internet. New Testament scholar Andrew Bernhard noticed that the online publishers had made a serious grammatical error in their work and that the same error is repeated exactly in the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.” Most recognized instantly that this error was the forger’s smoking gun, evidence that someone had “copy-pasted” quotes directly from the source material, rearranging them in a clever way and adding just a few words to suggest that Jesus had a wife. But Dr. Karen King and her supporters dug in their heels.

For support they pointed to a radiocarbon dating study that showed that the fragment was ancient, dating to the 8th century (not the 4th century as Dr. King had initially believed.) That in itself proves nothing because the papyrus was carbon dated, not the writing itself. Ancient papyrus can be readily bought online. A forger with the skill to make ink from ingredients that were available in the 8th century and who could obtain ancient papyrus could create a forgery that radiocarbon dating alone could not prove fraudulent. The results of the dating were reported in an article in the prestigious academic journal, “The Harvard Theological Review”.

A more serious blow to the credibility of the papyrus fragment was to follow. The “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” was not given to Dr. King by itself but it had come with another small scrap of papyrus that contained part of the canonical Gospel of John (Specifically John 5:26-31 on the front and John 6:11-14 on the back). The John fragment looked unremarkable at first. Multiple experts say that the two fragments are written in the same hand, using ink of similar composition and evidently even having been created with the same writing instrument. But the John fragment is written in an older dialect of Coptic called “Lycopolitan”. This dialect had died out by the 6th century. Remember that the results of the radiocarbon dating placed the origin of the fragment in the 8th century C.E . Simply put, no one was writing anything in Lycopolitan in the 8th century C.E.

Even that was not the most damning piece of evidence. A translation of a rare Lycopolitan Coptic papyrus text of the Gospel of John (discovered in 1923) was first published in 1924. This substantial work is now available online. Christian Askeland, Assistant Research Professor of Christian Origins at Indiana Wesleyan University noticed an unusual connection between the 1924 translation and the Gospel of John fragment. A comparison of the two showed that the one had been directly copied from the other. When one compares the Gospel of John papyrus with the Herbert Thompson text of 1924 (see image) the dependency of the one upon the other is immediately apparent. Every second line break (where the text begins) is identical. On the front of the papyrus and the back of the papyrus are 17 lines total. Christian Askeland writes, “Seventeen of 17 line breaks are the same. This defies coincidence.” The Gospel of John fragment is thus proved a fake. Since the “Gospel of Jesus’s wife” fragment and the Lycopolitan “Gospel of John” fragment were presented together to Professor Karen King by their anonymous owner and since they share the same handwriting and ink, if one is proven fake, than the other is as well.

Compare the forgery with every second sentence from the 1924 translation (underlined in red), including the line breaks. Image credit: Professor Mark Goodacre

The new evidence impressed Professor King, but she was not ready to throw in the towel, “This is substantive, it’s worth taking seriously, and it may point in the direction of forgery. This is one option that should receive serious consideration, but I don’t think it’s a done deal.”

Very few would have agreed with her at this point. Yet, the story still elicited curiosity. One reporter, Ariel Subar, was curious about the mysterious anonymous owner of the fragments. He decided to research not the fragments themselves, but their origin. The amazing story is detailed in a July 2016 article in the Atlantic Monthly. It’s a very entertaining article and well worth a read! Professor King was very cooperative and gave Subar the email correspondence she had with the anonymous owner (with his name removed) as well a photocopy of a sales receipt for the purchase of those fragments and a copy of a 1982 letter from an Egyptologist in Berlin who claimed to have examined at least one of the parchments. Professor King lamented in an article published in 2014, “The lack of information regarding the provenance of the discovery is unfortunate, since, when known, such information is extremely pertinent.”

The email correspondence, sales contract and letter did mention some names but when investigated they all proved to be quite unhelpfully deceased. The owner of the fragments who sold them to the anonymous owner was identified as Hans-Ulrich Laukamp, an East German man who purchased them in Potsdam, East Germany in 1963. Ariel Subar interviewed Laukamp’s surviving relatives in Germany. They pointed out that the story in the emails was near impossible as Laukamp had escaped from East Germany in 1962 by swimming across the border. When he arrived he possessed little more than his swim trunks. For him to have purchased the fragments in Potsdam meant he would have risked his freedom by going back to East Germany less than a year after his arrival in the West and then re-escaped back across the heavily guarded border. Further, none of his relatives could recall Laukamp as having been a collector of anything let alone rare Egyptian documents.

The letter from the Egyptologist was problematic. First, the address was wrong, didn’t even exist in fact. On top of that the letter bears a 1982 date yet uses a Berlin Egyptology Institute letterhead that the institute would not adopt until 1990. Clearly, even the story of how the fragments came into possession of the anonymous owner was a lie.

But who was the anonymous owner? Multiple lines of evidence pointed to a former business partner of Laukamp. That man was a West German immigrant to the United States named Walter Fritz. Fritz was an auto parts executive, a one time producer of pornographic websites (starring his wife) and tellingly, a university drop out who had studied Egyptology and the Coptic language. His wife had self-published a book of “Universal Truths” and claimed to be able to channel the voices of the angels. When confronted with the evidence that pointed in his direction Fritiz repeatedly denied ownership of the fragments. Finally, Subar confronted Fritz with evidence that he had registered a website called, gospelofjesuswife.com only weeks before Professor Karen King’s big announcement. Two weeks later, Walter Fritz admitted ownership of the fragments although he denied any knowledge that the fragments might be fraudulent.

Upon reading Ariel Subar’s article in the Atlantic Monthly, Professor Karen King allowed herself to be interviewed by Subar for a follow-up article. The evidence, she confessed, “presses in the direction of forgery.” As of the time of writing, the Harvard Theological Review (HTR), the prestigious “peer-reviewed” magazine that published Professor Karen King’s paper, still refuses to retract it. Retraction Watch, a website that reports on the retraction of scientific papers as a “window into the scientific process“, calls the HTR’s position “a cop-out of — bear with us — Biblical proportions“.

What have we learned?

The first thing we have learned is that the experts are not always correct and like anyone else, experts may be fooled. Even when multiple lines of evidence lined up against the fraudulent “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife”, some experts were willing to overlook that evidence because they wanted to believe. Why? The “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” fit in well with their world-view. It confirmed their biases. It confirmed their presupposition about the Bible being an entirely human work and not a book written under divine inspiration . Experts in fraud detection say that fraudsters often have a particular target customer in mind when creating a counterfeit. This may have been the case with the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife”.

We have also learned that “peer-review” is not a guarantee of accuracy and that even prestigious publications such as the National Geographic, the Smithsonian Magazine and the Harvard Theological Review can be quick to publish sensational articles regarding Biblical subjects, but slow or negligent to publish retractions when they prove to be less than factual. When the retraction does come, oftentimes it will be buried in a small article somewhere in the magazine significantly less prominent than the original article.

Inevitably, another headline grabbing “discovery” will promise that everything you know about the Bible is wrong or that the history of early Christianity will have to be rewritten. Treat such claims with a large dose of healthy skepticism and wait patiently for the rest of the story to unfold. The Apostle John warned the early Christian congregation, “Beloved ones, do not believe every inspired statement, but test the inspired statements to see whether they originate with God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world.” (1 John 4:1)

Footnotes:

*Author Salmon Rushdie wrote of the book, “A novel so bad that it gives bad novels a bad name.” Stephen King said the book is the “intellectual equivalent of Kraft Macaroni and Cheese“. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote,” I should read a potboiler like The Da Vinci Code every once in a while, just to remind myself that life is too short to read books like The Da Vinci Code.” The movie has a 25% rotten rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes.

** Dr. King is not a supporter of the Da Vinci Code theory and believes there is no evidence that Jesus was married or that he had children.

***What is the “Gospel of Thomas”? The “Gospel of Thomas” is a document that claims to contain a collection of the sayings of Jesus. Unlike the 4 Gospels of the Bible, it was not written by contemporaries or eyewitnesses of Jesus but was written in the 2nd century. It belongs to a family of documents written between the 2nd and the 4th centuries called, “Gnostic Gospels”. The Gnostics were an offshoot of early Christianity that taught things that were widely at odds with the teachings of the Apostles in the Christian Greek Scriptures. These pseudo-Christian writings have little, if anything to teach us about the historical Jesus.

Photo Credit:

“Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” Fragment. {{PD}} Wikimedia Commons

Forged Gospel of John fragment compared to the Herbert Thompson translation of 1924. Comparison created by Professor Mark Goodacre. Source: Mark Goodacre’s NT Blog.

Very interesting! You hear a lot about the original news release, but not to often do you hear the rest of the story.

oi vey!